A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE

NATIONAL HEALTH SERVICE (PART 3)

Difficult Teenage Years Before the NHS Comes Of Age 1958 - 1979

By the second decade, the NHS was beginning to settle down. Treatment was improving as better drugs were introduced. During this decade, the polio vaccine came in, dialysis for chronic renal failure and chemotherapy for certain cancers were developed.

Doctors' pay

There were, however, problems for both GPs and hospitals despite the development of a measure of trust between the professions and the Government. The Royal Commission on doctor's pay alleviated some of the arguments which had caused problems during the first decade. Negotiations between the Government and GPs leaders led to a review body award which provided a basis for the development of the modern group practice. Matters would come to head in 1965 with the GP's Charter and again the following year when pay structures were agreed.

Management and Structure

Better management became a priority. Hospital Activity Analysis was introduced to give clinicians and managers better patient-based information and divisions were created with the aim of grouping medical staff by speciality. Increasingly, though, the structure of the service was being criticised. Two reports, five years apart, would increase the pressure on Governments to address both the structure of the NHS and its future.

In the 1962 Porritt report, the medical profession criticised the separation of the NHS into three parts - hospitals, general practice and local health authorities - and called for unification.

1962 also saw the publication of the most important plan for the future of the NHS since Beveridge had reported to Churchill back in 1941. The person behind the plan, like many who followed, would ultimately lose his job because of his outspokenness rather than his ability to function as a Minister.

While much had already been done to appoint consultants in the major specialities throughout the country, their skills were not matched by the outdated and war-damaged buildings in which they worked. Enoch Powell's Hospital Plan, published in 1962, approved the development of district general hospitals for population areas of about 125,000 and in doing so, laid out a pattern for the future.

The ten year programme put forward was new territory for the NHS and it became clear it had underestimated the cost and time it would take to build new hospitals. But, a start had been made and with the advent of postgraduate education centres, nurses and doctors were given a better future.

The Plan demonstrated a growing emphasis upon the need to plan services within the NHS, as well as a faith in the ability of such planning to achieve greater efficiency and rationality in the use of NHS resources. Such an emphasis reflected the pressures on resources exerted by the rising costs of care. The reasons for such rises were debated. They included developments in medical technology and medical pressure to keep pace with such developments; rising expectations on the part of the population; pressures for higher wages and salaries within the service; and the demographic changes caused by an ageing population.

The Plan also sought to build on the advantages that the creation of hospital management committees had been able to bring to the organisation and planning of local hospital services.

The creation of a national health service, with national pay scales and conditions of service for hospital consultants, had helped to even out the distribution of hospital staff around the country. At the same time, however, professional gulfs between the hospital consultant and the general practitioner began to widen.

As the result of the Government's Hospital Plan, new hospitals were providing more people with a better and more local service. The organisation of hospital nursing services was changed by the Salmon Report and nurse education by Briggs, while the advent of information technology saw the first steps in health service computerisation and clinical budgeting.

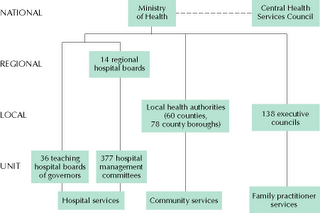

The Structure of the NHS 1948-1974

The Salmon report in 1967, detailed recommendations for developing the senior nursing staff structure and the status of the profession in hospital management. Then, also in 1967, the first report on the organisation of doctors in hospitals (known as the Cogwheel Report) proposed speciality groupings that would arrange clinical and administrative medical work more logically.

The variety of efforts being made at this time to reduce the disadvantages of the three part structure showed the growing acknowledgement of the complexity of the NHS and the importance of change in order to meet future needs.

By 1969, clinical and organisational optimism prevailed in the NHS, it had come of age, but the mood progressively receded until, by 1977, various factors had combined to bring the third decade to an unpromising close.

The End of Universality

Beveridge's dream of a Welfare State funded by almost full employment had promoted the idea ,or should that be ideal, of universality - whatever you paid in, however much or little gave you the same rights to treatment. It was a dream that was fading fast in the harsh economic reality of the 1960's. Whilst politicians were telling the public they'd never had it so good, behind the scenes was the realisation that some were havig it better than others.

In 1961 the Conservatives introduced the graduated pension scheme, the idea behind it was simple, those earning more could afford to pay higher contributions in exchange for higher benefits. In 1966 the Labour government, as well as overseeing England winning the World Cup, introduced earnings-related supplements for sickness and unemployment benefits.

The Welfare State was now in danger of providing a two-tier system with low basic benefits supplemented by National Assistance (Supplementary Benefit from 1966) for the poor and higher benefits for those better off who could pay more in contributions.

As the concept of real poverty was re-discovered in the late sixties so governments resorted to applying means tests for those in specific need and introducing rates rebates (via the 1966 Rating Act), new benefits for the disabled and very old (via the 1970 National Insurance Act) and Family Income Supplement in 1971.

The final nail in the coffin of universality would be Mrs Thatcher's decision to withdraw the provision of free milk for all children in state schools.

Medical progress

Despite all these problems medical progress continued, with advances including the increasingly wide application of endoscopy and the advent in 1971 of CAT (CT) (Computerised Axial Tomography) scanning as the service's investigative armoury was extended.

The original 1971 prototype took 160 parallel readings through 180 angles, each 1° apart, with each scan taking a little over five minutes. The images from these scans took 2.5 hours to be processed by algebraic reconstruction techniques on a large computer. Today 'Fifth Generation' scanners can construct a 1,000 image study in less than 30 seconds - a further example of how technological advances have impacted on the NHS. As an aside it is often been said that were it not for The Beatles, research into the first commercially viable CT system would not have been possible, the huge profits from their record sales enabled EMI to fund scientific research.

How's that for irony? Drug fuelled 60's musicians create profits allowing medical research to be funded.

The 1971 Prototype funded by

sales of Sgt.Pepper (who'd have

thought it!)

A modern CT Scanner

Transplant surgery was becoming increasingly successful, and genetic engineering slowly began to influence medicine. Intensive care units were now widely available for looking after patients requiring more detailed observation and treatment than in standard wards, with a high ratio of medical staff to patients and new drugs appeared, including for example non-steroidal anti-inflammatory treatments.

Kidney dialysis was introduced, today there are around 19,000 people receiving kidney dialysis in the UK. I can actually remember the excitement in our school when one of the pupils was allowed to leave hospital after a serious illness and told he could receive treatement at home via a 'portable' dialysis machine.

In the 1960's , thanks to the development of the heart-lung by-pass machine that takes over the function of the heart and lungs, open heart surgery became a practical and successful form of treatment for people suffering from heart disease. Today, open heart surgery has become 'routine' in hospitals which perform cardiac surgery

On the downside, new infections, such as Lassa Fever emerged, and when the Abortion Act came into force in 1967 it led to new pressures on gynaecological services.

The discovery in 1957 of chlorothiazide, the first effective oral diuretic, had been, probably, the most important advance in drug treatment since penicillin.40 People with heart failure could now live a much more normal life, at home, while under treatment. Other more potent compounds of the same group followed rapidly and in 1965 frusemide was a further improvement.The treatment of high blood pressure improved steadily with the introduction of new drugs. Rauwolfia, acting partly as a tranquilliser, was replaced by the oral diuretics often in combination with ganglion-blocking drugs such as mecamylamine, although these produced constipation, blurred vision and difficulty in urination. Adrenergic-blocking drugs (e.g. guanethidine) had fewer side effects, and early death from severe hypertension was now seldom seen. Angina was shown to be relieved by propranolol, a member of a new family of drugs, the beta-receptor blockers.

New Hospitals, G.P Charters and Right Wing Proposals

In general practice, the 1965 GP's charter was encouraging the formation of primary health care teams, new group practice premises and a rapid increase in the number of health centres.

The core of the Charter was the demand for the abolition of the 'Pool' a capitation system which was a means of securing equitable incomes among GPs with different numbers of patients on their lists. Rather than setting a specific rate for the job, the target net income for a GP was decided and then multiplied by the number of doctors. It was this calculation that determined the size of the 'Pool' from which GPs' pay and expenses were drawn. This was fine in 1951 when the scheme had been established but by the early 1960s, the population was rising faster than the number of doctors.

There were many other disadvantages of the Pool.

The amount paid for expenses was an average rather than a real sum, which rewarded those who did least to improve their practices, and the amount distributed from the Pool as income was in fact a residual because the amount GPs were expected to earn from outside earnings (for example, from hospital work and private practice) was deducted before doctors were paid. Thus those doing large amounts of hospital work effectively made their colleagues worse off.

By the mid-1960s, the BMA made it clear to government that 'there was no support for the Pool method of payment as at present constituted' and requested changes to ensure that the full reimbursement of expenses and a return to making patients rather than the number of doctors the basis for capitation payments. But the Charter was also careful to stress that acceptance of it would enable the doctor 'to give the best service to his patients', and BMA Council members stressed that the Charter was as much a patients' as a doctors' Charter

In 1966 GP's Contract achieved a standard capitation fee for 'normal' working hours and a higher rate for 'out-of-hours' work and for elderly patients; a 'basic practice allowance' to be paid in full to all principals with lists of over 1,000 patients; and fees for particular services. As a result, the percentage of the GP's income derived from capitation was reduced from about 60 to about 50%.

From 1968 to 1974 debate continued on the crucial question of how the NHS should best be organised. Key issues included local government reorganisation and the desire to improve the co-ordination of health and social services by matching the boundaries of health and local authorities.

A senior Tory with a fiercely right-wing reputation moved into the job of Health Minister in 1972. Keith Joseph, credited as the chief architect of Thatcherism and known as the "Mad Monk", also displayed more liberal tendencies when he was in charge of the NHS.

As soon as he was appointed by Ted Heath, he set about trying to reform the now bureaucratic and unwieldy NHS. He put huge energy into improving care for the elderly and the mentally ill, and won large increases in his departmental budget from the Treasury to carry out the task.

In 1973, he introduced the National Health Service Reorganisation Act, but was unable to see it through because of the 1974 General Election.

Keith Joseph effectively killed off his own ambitions for leadership with his infamous "pills for proles" speech in 1974 where he argued that too many children were being born to unfit mothers and that "our human stock is threatened." His solution was to suggest the lower social orders should be given better contraception. The speech caused uproar, saw him branded a fascist and eugenicist and led to him standing aside in favour of Margaret Thatcher in the 1975 Tory leadership election.

It was left to his successor, Barbara Castle, to implement his reforms which sparked an angry backlash amongst health workers and plunged the NHS into a period of intense industrial unrest.

Health Workers were particularly furious that the gradual introduction of pay-beds had, as they claimed, led to consultants using their services for fee-paying patients. Eventually, ancillary workers blacked private beds and Mrs Castle faced some of the most difficult years of the NHS' history.

She replied with one of the biggest reorganisations yet, creating the regional health authorities and family practitioner committees.

Pay beds were cut and private beds in NHS hospitals were phased out. However, consultants were allowed to take on private work - a move that led to the growth in private care in private hospitals. But, probably most significantly, nurses won a 58% pay rise.

Resources planning

What was also needed was a planning system to distribute resources more fairly and to improve management. Two plans fell by the wayside; the third was implemented in 1974, but not until the Government that devised it had been replaced in a General Election.

The new system soon earned criticism as too complex and managerially driven. Within two years, a Royal Commission on the NHS had been appointed to look into the problem areas.

Just as strategic planning, long-range forecasts and reallocation were introduced, inflation reached 26 per cent and wage restraint came in. Industrial action hit the NHS while consultants too were alienated by proposals to reduce private practice within the service.

The biggest change to the NHS since the 1962 Hospital Plan was just around the corner and its architect was to be somebody who at first had no idea what to do with Europe's largest employer.

to be continued.............................................

4 comments:

Where did you find all this info Baldinio?

And then to change subject completely

Did you know that one cannot find your blog through your blue Paul on the blogs,its not switched on.

Hope thats helpful...

:)

Hi Lucy

I'v used quite a few sources which I'll list at the end of the last piece.

Glad you are still reading!

Thanks again Paul. You fill in gaps in my knowledge for me and I find the series so far, fascinating. Loved the stuff about EMI. Where did you get that from?

The EMI profits story was on the radio and is also quoted in a couple of sources on the internet.

Post a Comment